From 2018-2020, the DC Storytelling System has been collecting local neighborhood stories directly from members of the community. Over the past two years, we’ve collected dozens of recordings that capture the history of DC and what it’s like to live in this city. Today, we would like to take a moment to share a couple favorites.

Clip #1: Phil Muse, Architect

Listen to Phil Muse, who works as an architect in Chinatown, and who saw the exhibition in person.

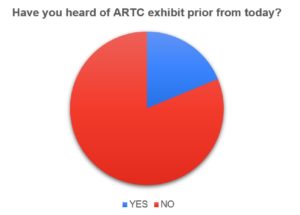

One simple goal of our system was to offer a means for gathering reflections on the show. We also posted callers’ stories to the hotline alongside excerpts from “A Right to the City” that were chosen by the show’s curators.

Clip #2: Godson of a Film Legend

The caller reveals he is the godson of legendary DC film producer “Topper” Carew (who was the creator of the hit TV series “Martin” starring Martin Lawrence, and behind hits like “DC Cab”). The caller shares memories of living, participating and playing music in the Adams Morgan community. The story was recorded live at the annual Adams Morgan Day Festival (where we brought a payphone!).

Topper Carew had already been featured in the Smithsonian show. However, the godson’s story revealed new details of how the family had persisted, and how the legend was being retold — including at street festivals and in ordinary conversation. In practice, our storytelling system simultaneously elevates some of the museum exhibition’s core stories to broader distribution, even as it makes for a more participatory process of hearing feedback on the stories and understanding some of their impact.

Clip #3: Shepherds of Shaw

Knowing the local neighborhood history can create a sense of place and collective identity. For D.C. resident John E. Richardson, Jr., his local church community in Shaw created a connection and identity that has made a lasting impact on his life.

The caller introduces the Shepherds of Shaw, a group of African American pastors in the Shaw neighborhood who played a pivotal role in providing affordable housing to their congregation and the wider community. The recording is a good example of how our system provides residents with a way to add their own frame to local history, and in their own voices. Such callers bring their own analysis of how local church leaders participated in creating a better community through community and housing development.

Clip #4: Linda Horton on Chinatown (and falling in love)

In this story, the love of a city and a specific person connect Linda Horton to D.C. — and Chinatown.

The story is a reminder of the many layers of connection and identity that are bound to neighborhoods, family, and identity. Callers who see their own family in the exhibition may be particularly motivated, and their reflections in turn bring new networks of interest. We see the storytelling system as a way of making more of these ties explicit by continuing to listen after the exhibition opens, and across institutions (like our listening stations at the front desk of DC libraries).

Clip #5: Betty B. of Brookland on 50 years of change

In this story, longtime D.C. Resident Betty Barksdale shares her story of Brookland as a changing neighborhood identity over 50 years.

Gentrification shifts the physical and mental landscape of a community. In this call, Betty describes how she moved to Brookland in 1964 and some of how it has changed due to urban renewal, as well as reminders of how modern institutions like Providence Hospital were once farmland. Local stories like Betty are important for historical preservation and creating community-led narratives.

Clip #6: Mt. Pleasant Library

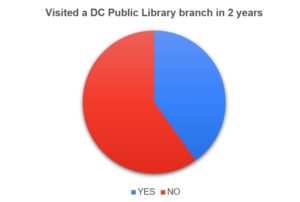

We were proud to install storytelling phones in the DC Public Library. In this story, a library patron shares how one library (the Mt. Pleasant branch) created a sense of belonging for her, tracing back to the the 1980s.

Libraries were just one of our “hubs” for storytelling. Taken as a group, we see the storytelling system as a kind of infrastructure for listening and sharing — to help situate history more immediately in community life across civic institutions.

Thank you to everyone that has called into the hotline and shared their stories.

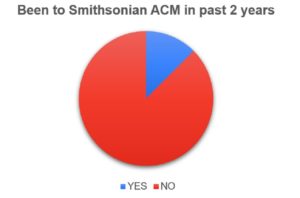

This project was made possible thanks to our incredible collaborators. Thank you to the Smithsonian Anacostia Community Museum, DC Public Library, the Leimert Phone Company, the Smithsonian Women’s Committee, American University’s School of Communication, the AU Humanities Truck, and the AU Playful City Lab.